Climate Change and Australian Food Security

- Friday, 27 June 2014

Jinny Collet

Research Assistant

Global Food and Water Crises Research Programme

Key Points

- Climate change is a key threat to Australian food security between now and 2050.

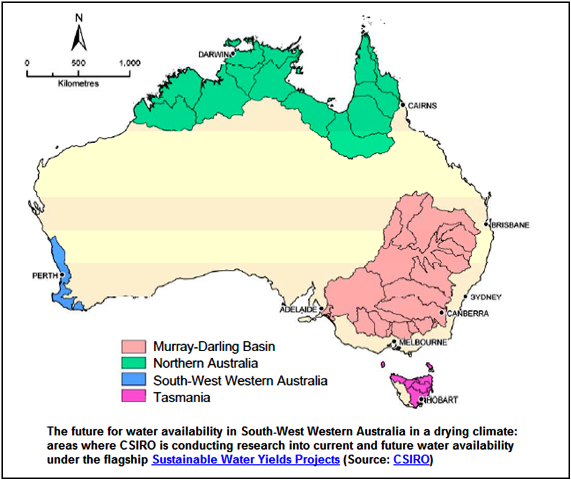

- The IPCC identified two major agricultural regions in Australia as climate-change hotspots: the Murray-Darling Basin and South-Western Australia

- Australia is at risk of falling behind its competitors when it comes to preparing the agricultural sector for emerging climate change impacts

- Australia needs to invest urgently in both adaptive and mitigative climate change research

Summary

Climate change is emerging as a key threat to global and national food security in the coming decades. Greater variability in rainfall, prolonged droughts and a greater incidence of extreme weather events are expected. In Australia, climate change has the potential to disrupt agricultural production and adversely affect the country’s ability to produce food.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) identified two areas in Australia, the Murray-Darling Basin and South Western Australia (two major agricultural producing regions), that will experience significant impacts from climate change. The Australian government’s plans to cut funding to climate change research, has increased the country’s risk of falling behind competitors who are investing with increasing urgency in research efforts to mitigate and adapt to climate change impacts. It is critical that Australia’s efforts to address climate change are redoubled, not reduced, if it is to meet future climate challenges.

Analysis

According to the IPCC, rising temperatures and more variable patterns of precipitation are expected under climate change. These climatic changes will dramatically alter agricultural production worldwide. While some parts of Europe and North America potentially stand to benefit from a warmer climate, for the majority of agricultural producing regions crop yields will fall.

Similar predictions of rising temperatures and changing rainfall patterns are also forecast for Australia and will specifically affect its major agricultural producing regions. This paper examines the potential impacts of climate change on Australian agriculture and on local and global food security.

Australia’s Contribution to Climate Change

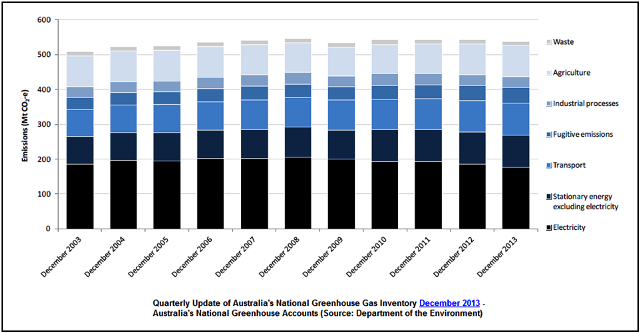

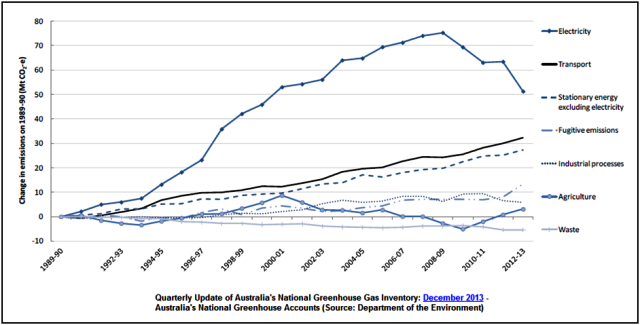

Australia is a significant global contributor to greenhouse gas emissions; per capita it is in the top ten of greenhouse gas producing nations. Reducing emissions is critical to mitigating climate change in the medium to long-term. According to Australia’s Department of the Environment, the biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions is the electricity sector (around 33 per cent last year).

Australia is a significant global contributor to greenhouse gas emissions; per capita it is in the top ten of greenhouse gas producing nations. Reducing emissions is critical to mitigating climate change in the medium to long-term. According to Australia’s Department of the Environment, the biggest contributor to greenhouse gas emissions is the electricity sector (around 33 per cent last year).

In 2013, approximately 17 per cent of national emissions came from the agricultural sector. Most of this (76 per cent) was from the expulsion of methane through livestock digestion. Greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture have been relatively constant over the past decade, fluctuating within 10 megatonnes of the 1989/1990 baseline. This highlights the need for a national response to reducing greenhouse gas emissions that would be adaptable to suit each sector.

Key Predictions for Australia

Historical long-term trends indicate that the climate in Australia is changing, with a tendency towards more frequent and more extreme hot weather events. Key predictions for the next two decades include hotter and longer summers, with rising temperatures and overall declining rainfall.

Conversely, some areas (including the north-west and north-east) will experience more intense rainfall which will result in increased incidence of flooding. Australia can also expect to experience growing pressure on urban water supplies and reduced availability of water for agricultural production.

Major declines in agricultural production are expected between 2050 and 2100, based on the results of climate change modelling. The IPCC, in its latest report, predicts changes to the climate in Australia are expected to continue for at least the rest of this century. The joint Bureau of Meteorology-CSIRO State of the Climate 2014 report indicates that current temperatures are, on average, almost one degree Celsius warmer than they were in 1910. Most of this increase has occurred since the 1950s, suggesting an accelerated warming trend.

Predicted changes in rainfall patterns

Changes in precipitation patterns are one of the key impacts of climate change and one of the most difficult to predict. In the long-term, however, with greater variations in rainfall patterns there is an increased likelihood of more extreme weather events. Australia will experience more frequent and more severe droughts and floods, with an overall rise in rainfall variability.

In Southern Australia rainfall will decrease, affecting major farming regions. For example, South-Western Australia and the Murray-Darling Basin, will witness precipitation declines by as much as 33 percent and 27 per cent respectively. Less certain predictions suggest increased rainfall and flooding in the tropical northern regions of Australia.

Predicted Rises in Temperature

In addition to changes in rainfall patterns, the IPCC also predicts increases in average land and sea temperatures across Australia. A hotter climate will increase rates of evaporation and transpiration, so that irrigated crops will require more water. Combined with reduced precipitation in some areas, this will exacerbate water demand and put pressure on farmers. Rising temperatures will also alter patterns of migration for many pests and diseases.

Meat and dairy production will be similarly affected. Rising temperatures will lead to a higher temperature-humidity index (THI), which is a measure of potential heat stress on livestock animals. The THI has been rising since the 1960s in the Murray dairy region; continued increases will cause a drop in meat and dairy output.

The occurrence of bushfires is also expected to escalate as land temperatures rise and the frequency of extreme fire days increases throughout the South-Eastern and South-Western regions.

Impacts on Australia’s Agriculture

Reduced rainfall in the South West will affect agricultural yields, including wheat, barley, oats and pulses. Those reduced yields will have global ramifications, as the region is a major exporter of agricultural products. As much as 80 per cent of the wheat produced in the South-West is destined for overseas, including Indonesia and the Japanese udon noodle market.

Water will be the limiting factor constraining agricultural yields. The South West is isolated from other irrigation areas, has no major river system and relies largely on farm dams and on-site bores. There is, therefore, less opportunity for water trading. Increased competition for water, especially near expanding cities including Perth, Bunbury and Busselton will further exacerbate the crisis and produce deficits in surface water irrigation catchments.

Reduced precipitation in the Murray-Darling Basin will also affect agricultural yields nationally and globally. The region grows most of the country’s rice and oranges, around half its wheat and apples, while also rearing approximately half its pigs. Other crops include cereals, fruit, nuts and vegetables, along with grazing pastures.

Wheat yields could fall by as much as 60 per cent in Victoria if current wheat cultivars are maintained. Similarly, in South Australia, by 2080 yields could decrease by as much as 30 per cent. In this scenario, Australia could go from being a net exporter of wheat to a net importer. Sugarcane and rice yields could also decline as both crops are water-dependent.

A threedegree Celsius increase in temperature (compared to the 1980-1999 baseline) is expected to reduce the value of beef production by four per cent; while the increase in the temperature-humidity index will also reduce meat output. Increased heat can reduce reproduction rates in cattle and lead to weight loss through diminished feeding.

As droughts become more frequent and intense, pasture yields will be adversely affected and grazing land degradation will become widespread. Pasture yield will also become less predictable and the quality of the pasture nutrients will decline, contributing to reduced livestock yield.

Implications for Future Food Security

Climate change represents a threat to future national and global food security. Australia currently produces 93 per cent of its domestic food requirements and exports 76 per cent of its agricultural products. On the global stage, Australia is a significant food producer, accounting for over 10 per cent of the global dairy export market and representing the third largest beef exporter behind India and Brazil.

Many Australian farmers are able to adapt to adverse weather events, but the strategies that they employ do not automatically lead to increased food security. Water trading, for example, allowed many farmers to survive the Millennial Drought in the Murray-Darling basin. The predominant pattern of fallowing rice crops to sell water, mostly to farmers in the wine-growing and horticultural regions, however, did not increase food production.

According to the Australian Agricultural & Resource Economics Society (AARES) report on the drought’s economic impact, the prices for many agricultural commodities rose significantly, including dairy, meat, rice and other cereals. Rice production dropped from 1643 kilotonnes in 2001 to 18 kilotonnes in 2007-2008 and the price more than doubled during this period. The drought also coincided with the 2008 global food crisis. As the frequency and severity of droughts increase, global crises are more likely to occur as multiple food-producing regions are simultaneously affected.

Water will become the limiting factor for agriculture as precipitation continues to fall in many agricultural regions. Intense competition between sectors with varying levels of purchasing power will further intensify the problem. This will leave less water available for farmers.

Adaptation to Climate Change

Adapting to climate change will be crucial to ensuring food production and farmers’ livelihoods are not adversely affected. At present the government has in place strategies to promote such adaptation. They include: securing urban water supplies through the use of grey water systems; desalination and waste water recycling, to reduce the competition for water between agriculture and other consumers. Further adaptations, including crop variations, changes to seasonal planting times and increased irrigation efficiency, will reduce potential impacts and losses.

Murray-Darling Basin: a case study of Australian farmers’ short-term adaptation

The Murray-Darling Basin Authority was set up to specifically address water security in the basin. The region is an important centre for agricultural production and part of the authority’s charter is to manage the basin’s natural water resources in a sustainable manner and in the national interest. This includes monitoring water usage and facilitating trade.

During the Millennial Drought, water trading allowed some crop yields to remain fairly stable as others plummeted. Output for water-intensive, but marginal, rice crops dropped to almost zero at one point. The water saved was sold to other farmers to produce higher-value perennial crops such as fruit and wine grapes.

Increased water efficiency was another method that demonstrated the ability of Australian farmers to adapt to changing conditions. Estimates indicate that efficiency per gigalitre of water more than doubled by the end of the drought. In the dairy industry, for instance, farmers purchased feed as a replacement for on-farm irrigation, which left many farmers with excess water that they could sell to other farmers.

Australian farmers can learn from the strategies other farmers around the world are adopting, as they too struggle to adapt to climate change. These include switching plantations from bananas to pineapple (more resistant to diseases and pests) in Uganda, or from corn to sorghum in the American Midwest. Greater flexibility in seeding times, drought-resistant crops, shorter production times to harvesting, switching from rain fed to irrigated agriculture and increasing water use efficiency, are all adaptation strategies to reduce vulnerability.

Climate Change Mitigation

Australia also needs to reduce its greenhouse emissions and mitigate climate change impacts. As one of the top ten emitters of greenhouse gases per capita in the world, there is considerable scope for reduction. This, however, is not straightforward. There is currently a lot of political uncertainty about the reality of climate change and somewhat of a governmental leadership vacuum on establishing a national mitigation strategy.

Businesses are key greenhouse gas emitters across all industries. If Australia is serious about reducing emissions and mitigating climate change, it is crucial that the business sector is involved in developing strategies. In the absence of serious governance, however, it is questionable whether businesses will act on their own to reduce their emissions.

Looking globally, some wealthy corporations are already vulnerable to climate change. Coca Cola is struggling in a lucrative, but drought-ridden market, to find the water it needs to manufacture its soda; Nike is concerned with the irregularity of cotton availability in South-East Asia.

Companies facing direct challenges due to climate change, have a more pressing incentive to act. In Australia, many companies are already exposed to the vagaries of climate change. In 2011, floods in Queensland disrupted coalmining operations, leading to losses of at least $5 billion. It is not only businesses operating outdoors that are at risk; the Brisbane business district closed down due to the flooding, which resulted in significant losses.

In the face of these challenges, Coca Cola and Nike have chosen adaptive rather than mitigative actions (for example, increasing water efficiency and switching to synthetic fibres). The business reality is that companies operate within timeframes focused on the present and near-future rather than long-term outlooks. Strategies for dealing with climate change are therefore similarly focused on addressing threats to the individual business within the same contracted timeframe.

While businesses should consider the mitigation of climate change as of the utmost importance, it is unrealistic to expect Australian companies to act on behalf of all Australians by reducing emissions without government incentives or legislation. At best, Australia can expect those adversely affected to take adaptation measures when threatened. Many businesses are in fact stridently opposed to mitigation legislation.

The Australian Chamber of Commerce and Industry, the Australian Industry Group, the Business Council of Australia and the Minerals Council of Australia, recently released a joint statement urging Parliament to repeal the carbon tax. Their concern was about paying more under the existing scheme compared to competitors elsewhere; thus they were focusing on pressing threats to business, rather than on long-term threats from the effects of climate change.

The agricultural sector, on the other hand, is in a good position to contribute to mitigation efforts. The Carbon Farming Initiative provides farmers with the opportunity to earn carbon credits. After storing carbon or reducing emissions on their farms, the farmers can then sell these credits to other businesses seeking to reduce their own emissions.

The Carbon Farming Initiative covers programmes that seek to avoid emissions of methane from a number of sources, including the digestive systems of livestock, the burning of vegetal matter or from rice cultivation. Projects that aim to store carbon (in living biomass, dead organic matter or in the soil) are covered as well.

The success of these projects depends on government and market influences. Storing carbon in the soil, for example, involves the addition of organic matter, such as biochar or organic residues, to the soil. This can be combined with practices like no-till, to reduce the rate of decomposition to carbon dioxide. Many farmers have taken up these opportunities, but there are limitations,which include limited water, but especially the cost of the organic matter to be added to the soil, making the practice subject to carbon initiatives and carbon prices.

Research and Investment in Climate Change Adaptation and Mitigation

Previous research funding has been devoted to many practical preventive strategies. These strategies include developing new wheat cultivars that are more resistant to extreme temperatures, or the CSIRO’s modelling of alert and sleeper weeds to predict new patterns of infestation in a changing climate.

Research funding has been used to allow long-term planning, which is a key requirement in view of the long-term impacts expected from climate change. The CSIRO thus puts a premium on identifying regions that are already marginal, for example warmer dairy-producing regions or drier crop-growing regions, so that strong policy can be implemented in time. Funding is also used to advise on mitigative opportunities for farmers, such as carbon sequestration and farming for energy provisions.

Identifying Gaps: Where further Research and Investment is Required

In the recent federal budget, the government announced a reduction in funding to climate change-related programmes from $5.75 billion this fiscal year to $500 million by 2017/2018. This means that there will be ten times less money available to devote to preventive strategies. At a time when urgent action on climate change is required more than ever, this is a blow to industrial and agricultural sustainability.

Australia is at risk of falling behind its competitors. The United States Department of Agriculture (USDA) continues to fund research that is focused and specifically targeted, including research on more adaptive water management for cattle production, as well as the development of more drought-resistant cattle breeds. Examples of crop research projects include investigations into the effects of climate change on pollinator bees and their parasites.

The USDA recognises that climate change represents an unprecedented threat to the country’s agricultural capacity and that the preventive strategies adopted will have a significant impact on the final outcome.

The United States is also committed to mitigative actions. More than two-thirds of the US$77 billion federal expenditure on climate change was invested in technology research, specifically to develop and deploy green energy. The US is also committed to helping other nations deal with climate change, with a considerable eight per cent of this expenditure funding overseas climate change initiatives.

Australia is also at risk of being left behind in the energy sector. As Australia procrastinates on how best to implement climate change mitigative actions, other nations, including the United Kingdom and China, are - like the US - increasingly investing in clean energy. These nations are assessing the situation realistically and, as a result, possess the foresight to realise that their future energy needs must be met by sources other than coal. Delaying investment now can only result in more exorbitant cost in future.

Conclusion: Australia’s Future Food Security under Climate Change Predictions

The IPCC predicts more frequent and severe droughts for the Murray-Darling Basin and for South-Western Australia, over the rest of the century. These changes are already underway, more noticeably in the Australian South–West where rainfall has been declining sharply since the 1970s.

Climate change will reduce crop yields in these two agricultural regions. The problem will be further exacerbated by predicted higher temperatures, which will increase the need for irrigation even as rainfall decreases. Higher temperatures will also increase heat stress on animals in certain regions (reducing meat and dairy outputs) and will adversely alter the distribution of weeds, pests and diseases.

The effects of climate change on agriculture will be felt worldwide, with wheat and rice prices expected to double by 2050. Australia is a major food exporter, so it is imperative for both national and global food security, that Australia act to reduce the impacts of climate change.

Australian farmers currently employ a number of strategies to adapt to climate change, including swapping crops, reducing water inefficiency and water trading, to help them through intense droughts.

Australia is, however, at risk of being left behind by its competitors. Current policies suggest Australia is out of step with the rest of the world on climate change, reducing funding to climate change research at a time when the US and New Zealand are investing with more urgency.

The government needs to resolve the uncertainty surrounding the Carbon Tax and must provide firm leadership on climate change mitigation. Adaptive actions against climate change will not be sufficient; Australia also needs to take mitigative action by reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

*****

Any opinions or views expressed in this paper are those of the individual author, unless stated to be those of Future Directions International.

Published by Future Directions International Pty Ltd.

80 Birdwood Parade, Dalkeith WA 6009, Australia.

Tel: +61 8 9389 9831 Fax: +61 8 9389 8803

E-mail: This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. Web: www.futuredirections.org.au